Kruse et al. 2017

The Asian citrus psyllid is the vector for the bacterium associated with citrus greening disease, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas). CLas is spread by psyllids through a process called circulative transmission. This means that as the insects feed on plant sap, CLas moves into the insect gut and crosses it to exit into the hemolymph (insect blood). It circulates in the blood and finally reaches the salivary glands to be spit back into the next host tree. Kruse and her colleagues were interested in how CLas interacts with the gut to cross into the blood and be transmitted, and if the presence of CLas causes changes in the cells of the gut.

To find out, researchers at the Boyce Thompson Institute and Cornell University began with hundreds of dissected guts from psyllids feeding on either healthy or CLas-infected citrus plants. They analyzed their transcriptome (the genes being expressed in these tissues) and proteome (the proteins present in the tissues). This gives a snapshot of the activity in gut cells when CLas is present.

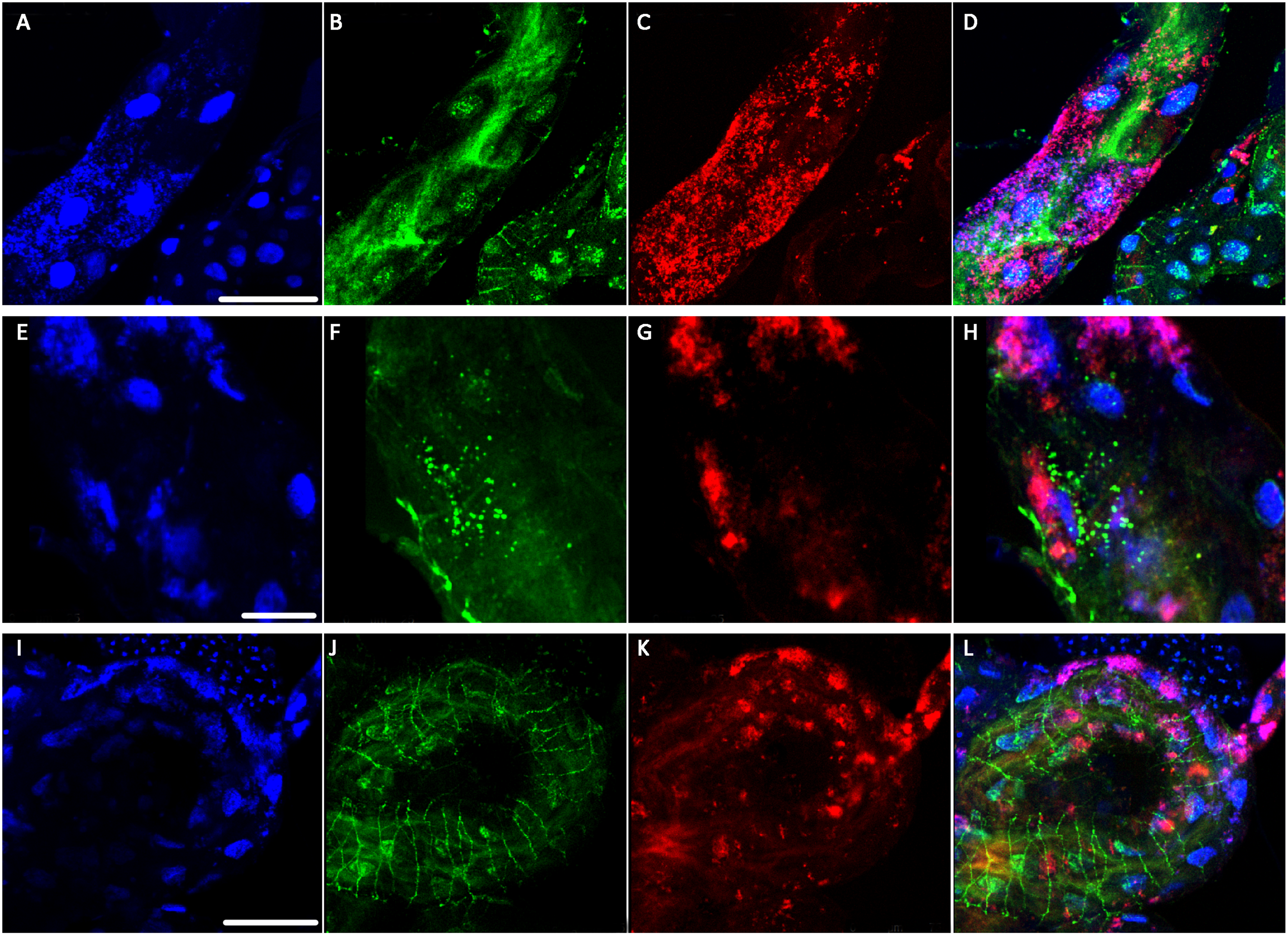

Kruse et. al. found that when CLas is in the insect gut, gut cells cannot make as much cellular energy. This became clear when they saw changes in the cycle that mitochondria use to make energy-it's called the citric acid cycle (Figure 1). Almost every protein in the cycle was effected by CLas! The gut cells also seem to react to CLas as a threat, rather than just a hitchhiker traveling from tree-to-tree. The cells mount an immune response to CLas. The cells even produce some defensive proteins that contribute to insecticide resistance.

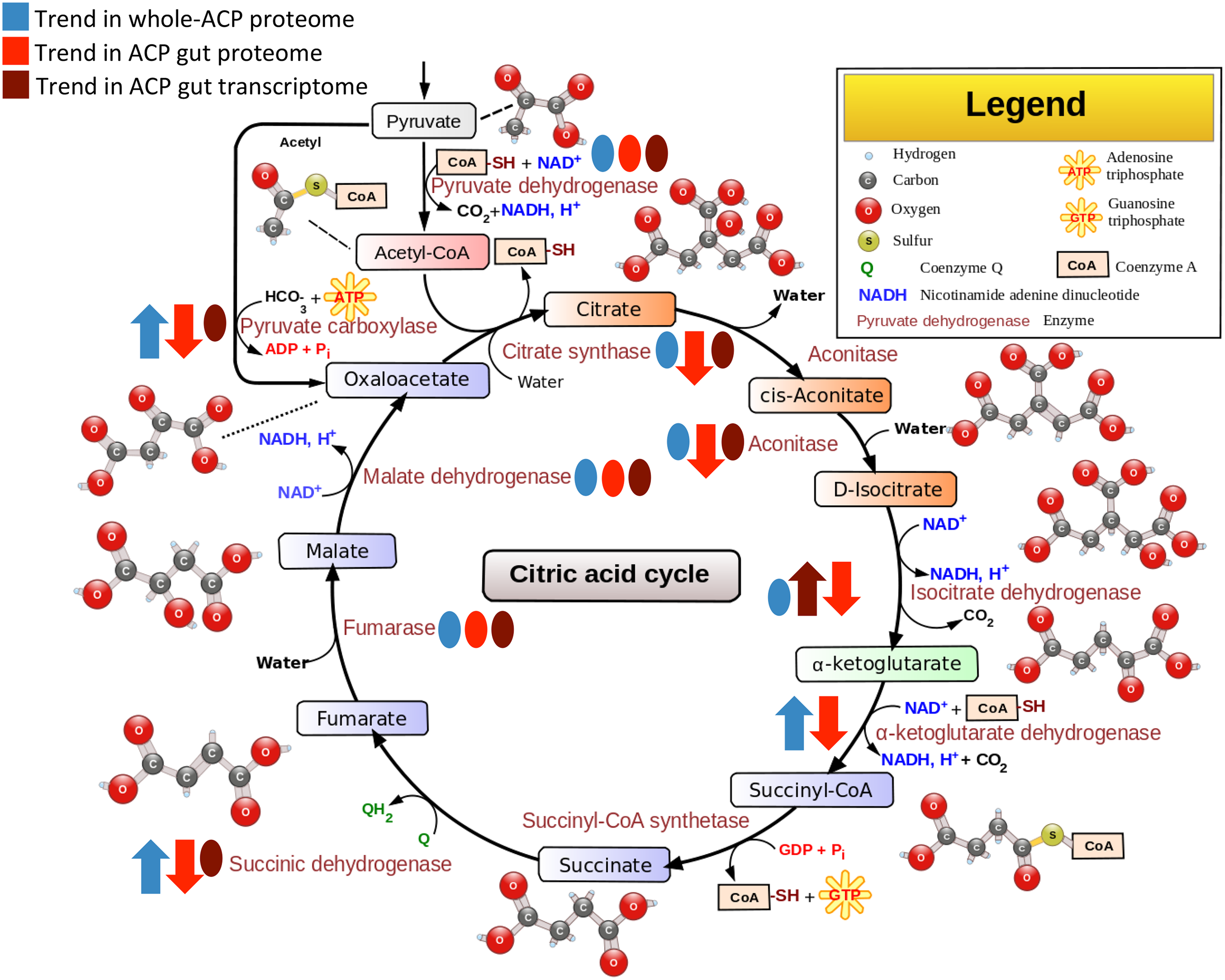

The researchers also used a confocal microscope to look at specific bacteria inside the psyllid guts. They used probes which tag bacteria with a colored fluorescent molecule. This way, they could tell different bacteria apart and see exactly where they are. They used a green probe for CLas (Figure 2B), and a red probe for a symbiotic bacteria called Wolbachia that is always in the psyllid gut (Figure 2C). The cell's nuclei were labeled in blue (Figure 2A). They found that CLas enters psyllid gut cells. They also saw that Wolbachia and CLas can be in the very same gut cell, but they never seem to overlap (Figure 2D). This suggests that Wolbachia and CLas are either competing or cooperating within the psyllid. This begs the question-could Wolbachia be a potential tool in the fight against CLas, or are Wolbachia and CLas partners in crime? To read about these findings in more detail, find the full article at Plos One.